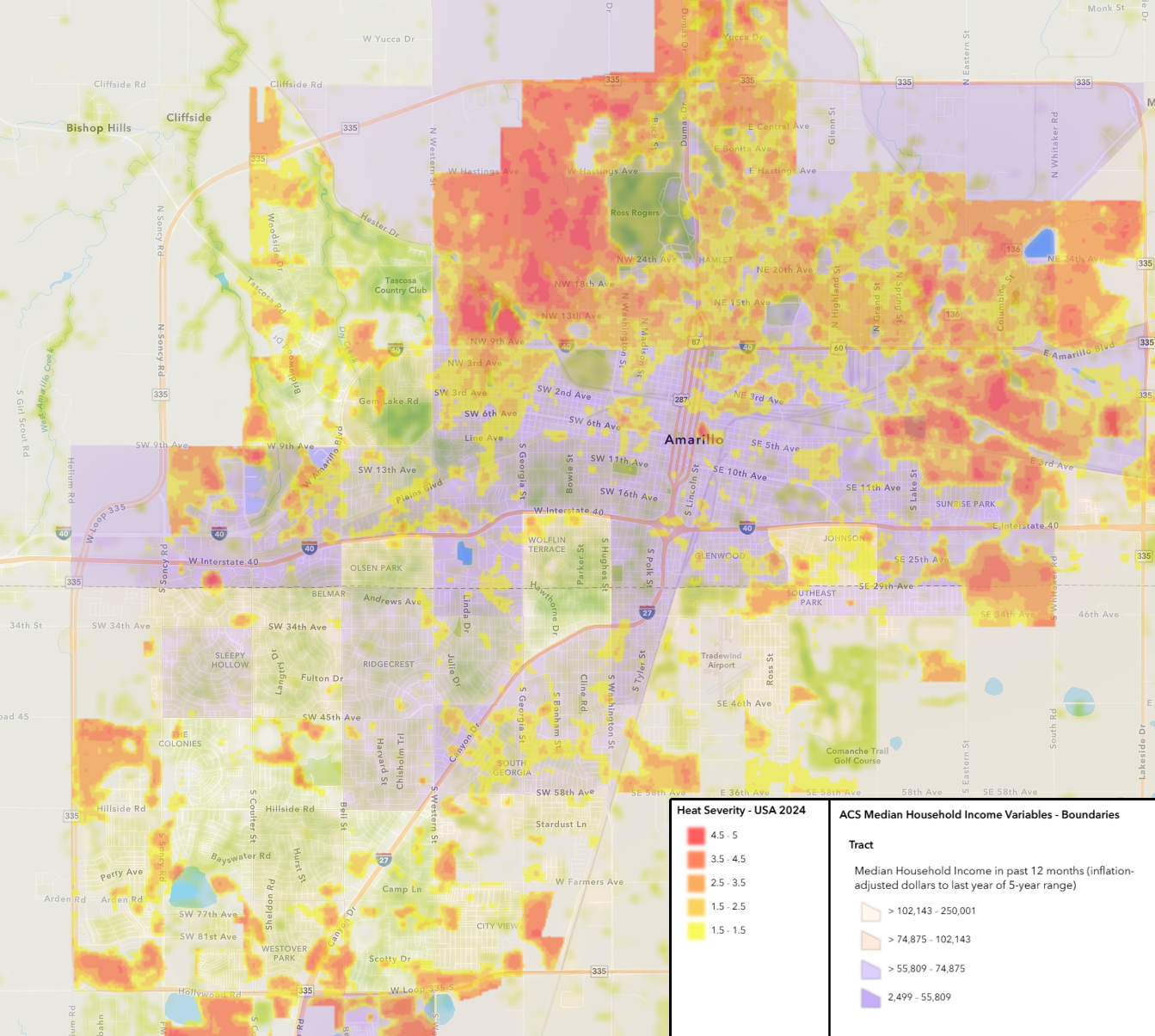

Asphalt is Cooking Amarillo (and the simple fix we’re ignoring)

I am excited to share my first GIS project! What better place to start than in our city of Amarillo? I explored Amarillo’s urban heat island effect in relation to tree canopy and household income. The pattern that emerged was striking. Neighborhoods with more pavement and less tree cover lit up as red hot zones. The pockets of mature trees standout like cool oases in a landscape of asphalt.

When household income is layered onto tree canopy and land surface temperature, the story becomes one of inequity as much as climate. Studies of thousands of U.S. municipalities show that low‑income neighborhoods have, on average, about 15% less tree canopy and are roughly 3 °F hotter in summer than higher‑income neighborhoods. That extra heat is not just uncomfortable, it translates into higher energy bills, greater strain on health, and increased risk for heat‑related illness and death (earthobservatory.nasa). Amarillo’s story fits into this broader national pattern that the residents with the fewest financial resources are often those facing the greatest impact from poorly designed built environment and climate change.

What are Urban Heat Islands?

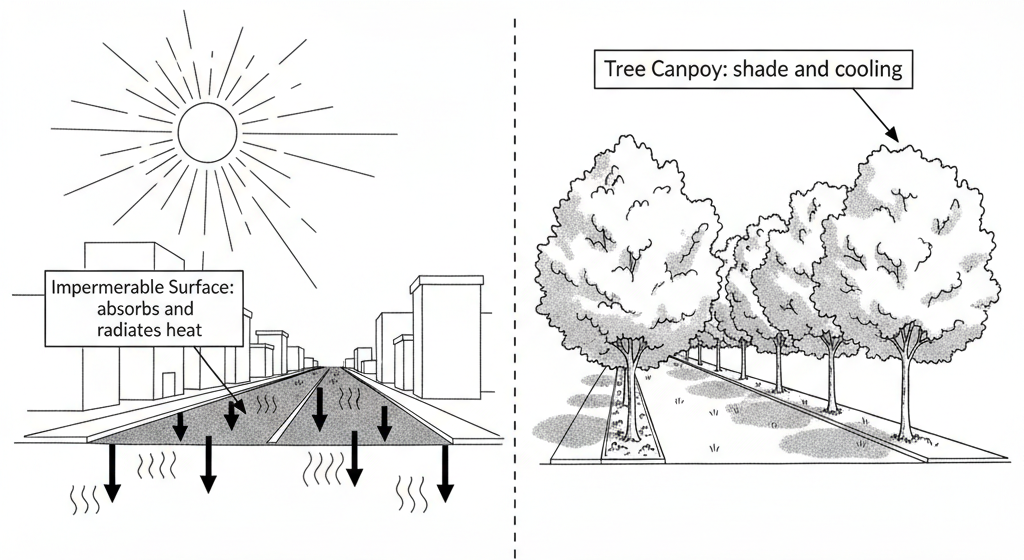

Urban heat islands form when natural land cover is replaced by dark, hard surfaces like streets, parking lots, and large roofs, that absorb solar energy during the day and slowly release it at night. Impervious surfaces like asphalt and concrete do not allow water to infiltrate, so they lose the cooling effect that comes from evaporation and healthy soils. At the same time, vehicles and air conditioners add waste heat directly into the urban environment, compounding the problem (surfrider).

Tree canopy, vegetated bioswales, and other green infrastructure work in the opposite direction, they shade surfaces, deflect some of the sun’s radiation, and release water vapor into the air, all of which help lower ambient temperatures. As a result, neighborhoods with abundant trees and green space can be several degrees cooler than adjacent areas dominated by bare pavement.

This heat difference shows up directly in household budgets and public health. Cooler neighborhoods need less air conditioning, which reduces energy bills and power plant emissions, while hotter, treeless neighborhoods lead to higher electricity use and greater risk of heat‑related health impacts.

What is green infrastructure?

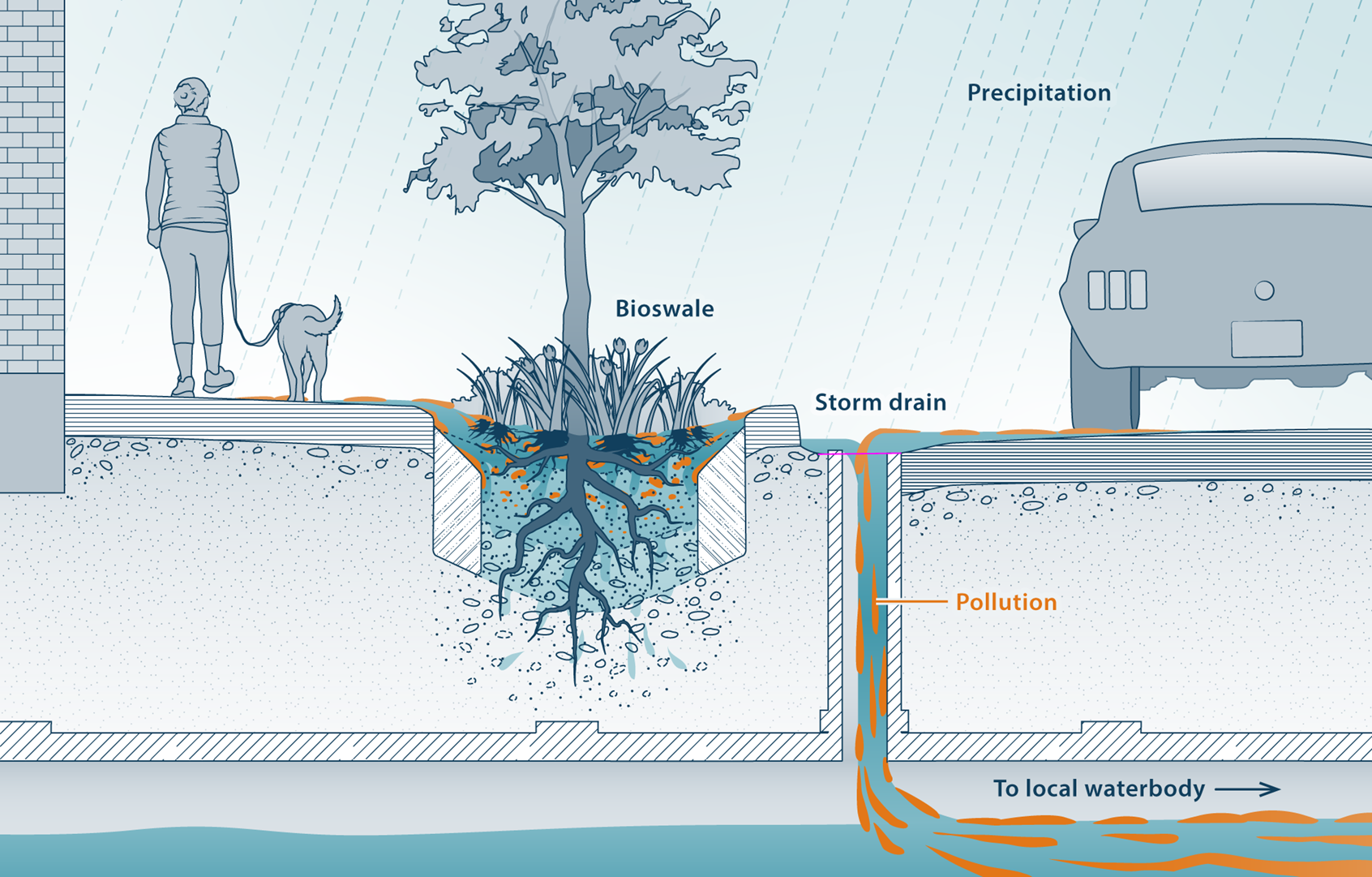

Green infrastructure is a broad term for infrastructure that uses soil, vegetation, and natural processes to manage stormwater, cool cities, and improve air and water quality. Instead of relying only on underground pipes and oversized channels, green infrastructure spreads water out across the landscape and lets it soak in, be filtered, or be slowed down.

An article I suggest you check out that does a great job of describing these solutions: Guide To Green Stormwater Infrastructure

Example green infrastructure elements that Amarillo can use to address both heat and flooding include:

Street trees

Rows of trees along streets, in medians, and in small neighborhood “pocket forests” create shade, improve air quality, and intercept stormwater. This has the extra benefit of helping slow car speed down which encourages active transportation like bikes!Bioswales and rain gardens

These are shallow, vegetated channels or landscaped depressions that collect and infiltrate runoff from streets and parking lots, reducing peak flows and filtering pollutants.

While individually these solutions may be small, they do add up. What I find fascinating is that when you zoom in on the map in the smaller yellow/orange heat pockets you’ll see that in that specific portion of the neighborhood/street there is less vegetation than the surrounding area. So even on a small scale the difference is measurable.

Long‑term savings for the city

Not trying to hide the upfront cost, retrofitting costs money, but cities should plan for the next generation, not the short term. Green infrastructure financial strength is in long‑term savings and avoided costs. Because rain is captured and infiltrated where it falls, peak flows to drainage systems are reduced, which can delay or eliminate the need to upsize expensive storm sewers. When we are currently facing water infrastructure problems that cost MILLIONS of Dollars it seems to me that adding more trees would help our stormwater problem and many others.

Beyond direct stormwater savings, green infrastructure lowers building energy demand by shading roofs and walls, cooling ambient air, and reducing the urban heat island effect. Less electricity needed for air conditioning means reduced operating costs for households, businesses, and public buildings, and fewer emissions from power generation. Trees and vegetation also capture pollutants and improve air quality, which can translate into lower health costs over time.

This article gives some estimates on cost: Implementation and Costs

What does this have to do with Bikes?

I know you’re asking yourself, “Great stuff, Chris, but what does this have to do with walking and biking?” Green infrastructure and active transportation are two sides of the same coin, the same street designs that cool and drain the city also make it safer and more appealing to walk and bike. When streets are cooler it makes being outside the car more comfortable.

Green streets are also generally safe streets. Most green infrastructure lives in the street whether it is curb‑out bioswales, tree strips, or landscaped medians, these features also naturally calm traffic by acting as visual friction. So not only do we have less flooding, reduced heat island, but also reduce crash risks for automobiles and create a safer, more inviting environment for people on foot or bike. So next time you’re out and about think about how all that excess asphalt is costing tax payer money and could be replaced with a bioswale or tree strip to create an opening for better sidewalks, protected bike lanes, and safer crossings.

What it would take to get there

Moving Amarillo toward greener, more sustainable infrastructure will require coordinated policy, funding, and design decisions, but the tools are already available.

Key steps for a city like Amarillo could include:

Updating stormwater and street design standards to require or strongly prefer green infrastructure where feasible.

Prioritizing tree planting and green infrastructure investments in the hottest, least‑shaded, and lowest‑income neighborhoods to address both heat and equity.

Integrating green infrastructure into transportation projects like turning medians, curb extensions, and excess asphalt into bioswales, tree lawns, and permeable plazas.

By consciously redesigning streets, parking lots, and public spaces to minimize impermeable surfaces and maximize green areas, Amarillo can cool its neighborhoods, reduce flood risks, and save money over the long term. My map makes clear where the problems are and that green infrastructure is the solution that can be both financially prudent and deeply transformational for neighborhood life.

Until next time, Ride Bikes, Plant Flowers.

-Chris Pittman